From the establishment of the Thirteen Colonies, territorial expansion was key to the formation of the United States. The gains made during the MexicanAmerican War (1846–48) extended the country’s boundaries from coast to coast. As the United States grew, the establishment of new territories and states displaced Native American nations and Native lands through treaties—but also through coercive means, purchase, and war.

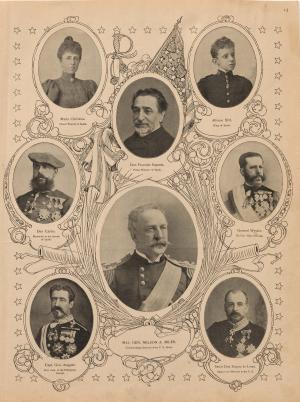

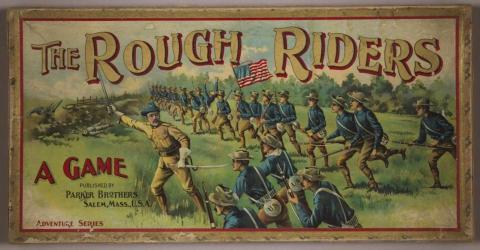

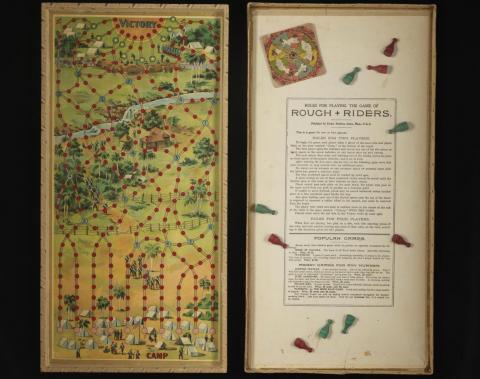

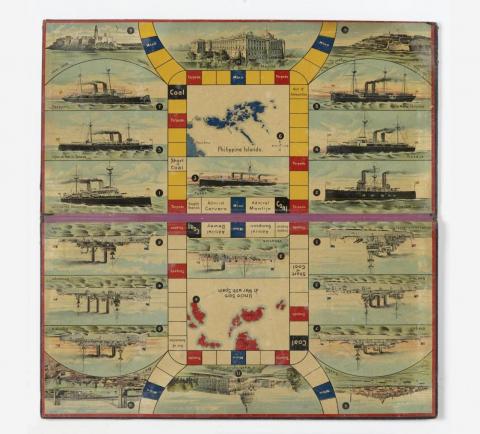

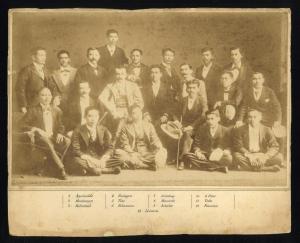

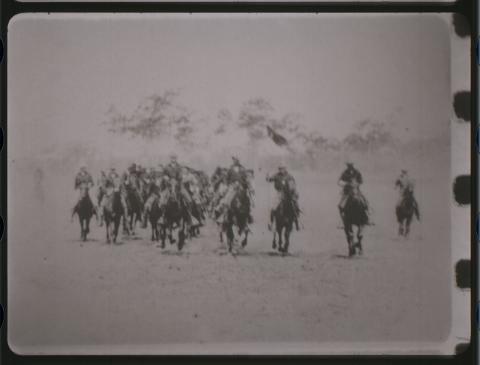

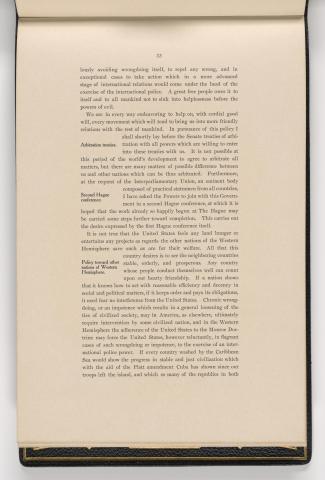

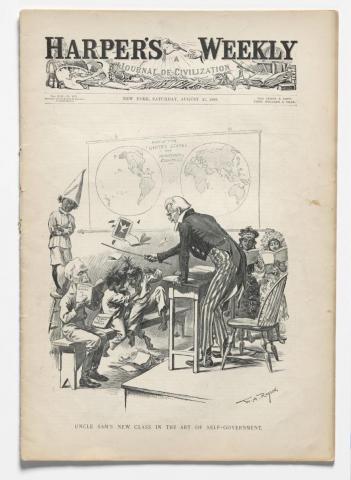

The Indian Wars of the 1870s became training grounds for U.S. military personnel involved in the War of 1898 and the Philippine-American War. Twenty-six of the thirty generals who served in the Philippines between 1898 and 1902 had some military experience in the West during the campaigns against Native Americans. U.S. governance in the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico was modeled on policies designed to restrict or strip away Native American rights.

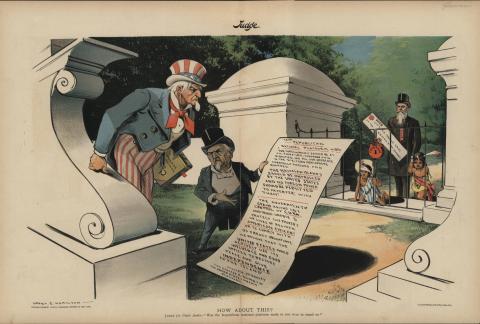

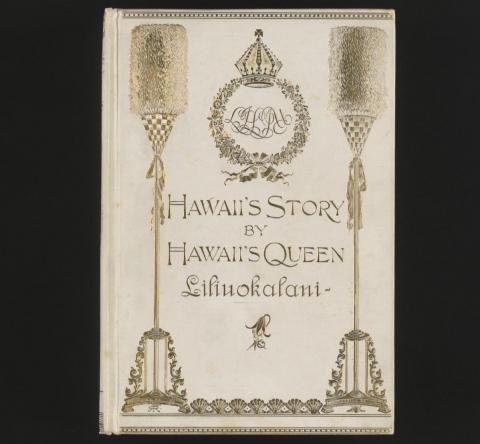

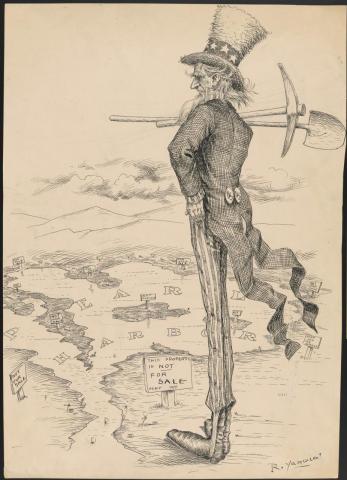

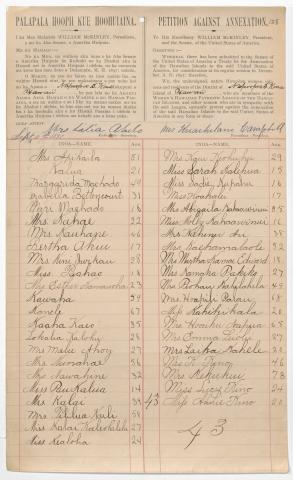

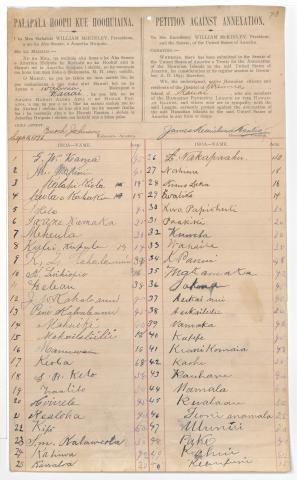

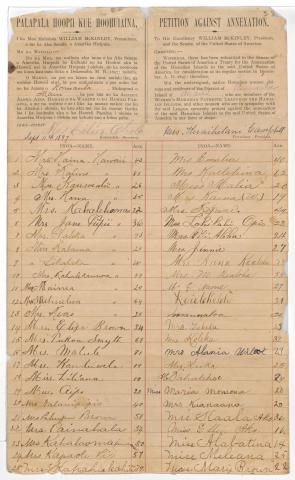

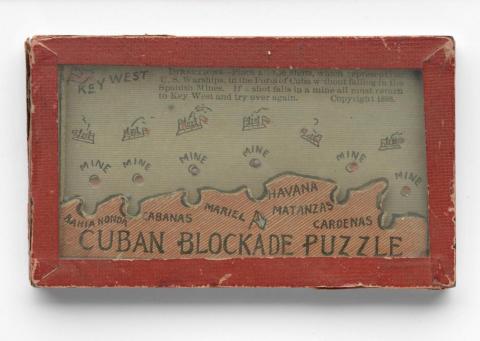

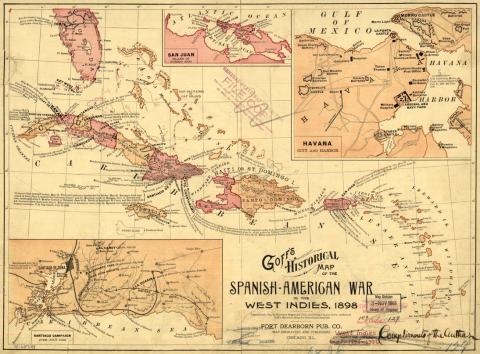

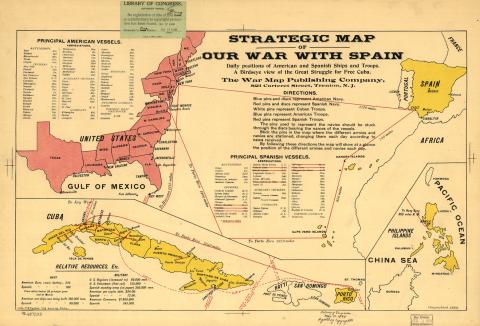

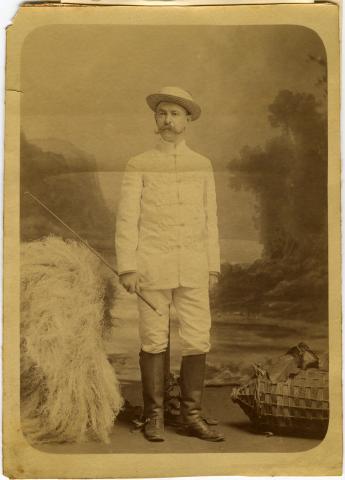

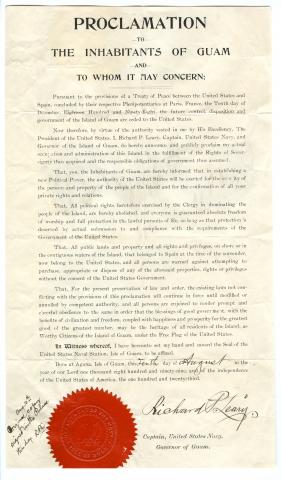

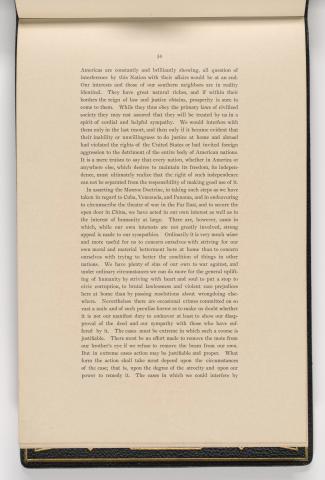

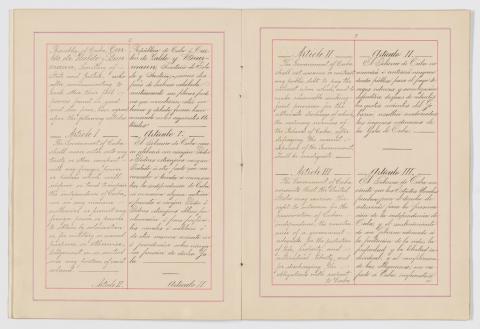

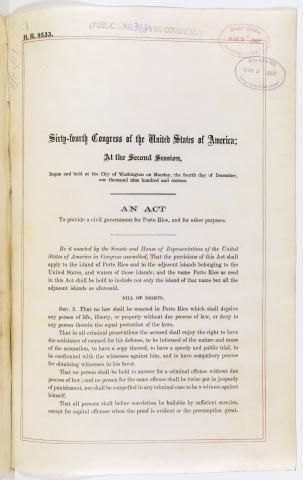

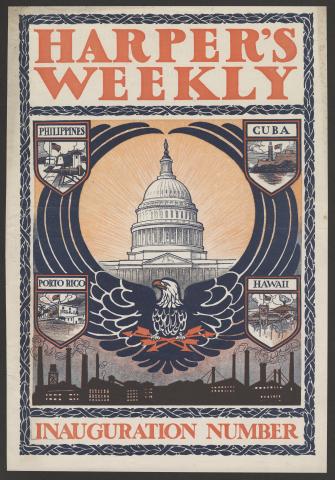

Powerful politicians believed that seizing territories overseas would transform the country into a world leader. In 1898, after decades of AngloAmerican presence in Hawai‘i, and as Cuba waged its last War of Independence, naval policy makers and legislators pushed for U.S. expansion into the Caribbean and the Pacific.