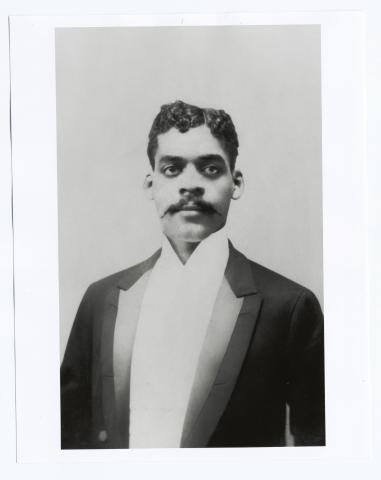

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (Arthur Schomburg) (1874–1938)

After Spanish authorities quelled the Grito de Lares rebellion (1868) in Puerto Rico, the island’s movement for independence primarily operated in New York City. As a hub for political exiles from Cuba and Puerto Rico, New York was home to organizations of Antillean solidarity. In April 1892, on the heels of Martí’s establishment (also in New York) of the Partido Revolucionario Cubano, the Afro- Puerto Rican typesetter Arturo Schomburg helped Afro-Puerto Rican Rosendo Rodríguez and the Afro- Cuban Rafael Serra in founding the political organization Las Dos Antillas.

Schomburg became the secretary to the organization that vowed “to assist in the independence of Cuba and Puerto Rico” through financial contributions and donations of weapons. Schomburg’s early experience in envisioning an antiracist and anticolonial political future for Cuba and Puerto Rico was formative in his career as a scholar of the African diaspora. His vast library laid the foundation for New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Audio Transcription: One of the most powerful dimensions of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg's life is that he was a person that was denied formal education, yet he made it his life's mission to educate the world about Black history. Schomburg migrates to New York City at age 17. The moment that he arrives, he becomes active in the networks of people from Cuba and Puerto Rico, men of color, involved in the pro-independence struggle from Spain. So if we look at Schomburg's arc, we see that he begins as a young man invested in building nations that have been subjected to colonialism for hundreds of years. But in 1898 the U.S. invades both Cuba and Puerto Rico, and Schomburg starts to become very skeptical about nation-building as a protector of Black rights. Schomburg begins to develop the idea that it is very important for Black people everywhere in the world to have a shared memory of being Black, that Black history was global, and that Blacks had a common investment in knowing that history. At the time that Schomburg was advancing these ideas-- the importance of Afro-Latino history, both in the United States and in Latin America, and of a long lineage of Black history in Europe-- most people were not receptive. But 100 years later, not only are his ideas well received, they're flourishing, no? They're shaping the way that we think about the world.

– My name is Frances Negrón-Muntaner. I am a professor at Columbia University in the areas of Caribbean and Latinx studies.